The Atomic Settlement Paradox: Why Faster Markets May Mean Less Liquidity

January 27, 2026

5 min read

In the rapidly evolving landscape of fintech and digital assets, the industry has rallied around a singular, inevitable goal: T+0, or "Atomic Settlement." From the US equity market’s move to T+1, to the proliferation of stablecoins and RWAs, the consensus is clear: settlement should be instant, final, and programmable.

However, beneath this technological optimism lies a counter-intuitive reality that few are addressing. While T+0 eliminates counterparty credit risk, it inadvertently introduces a massive drag on capital efficiency. This is the Atomic Settlement Paradox: When trades settle instantly, it costs market makers more to keep cash ready, leading them to charge higher fees and offer less liquidity.

The Mechanics of Efficiency: Netting vs. Gross Settlement

To understand this trade-off, one must compare Deferred Net Settlement (DNS) with Real-Time Gross Settlement (RTGS).

In traditional T+2 (and even T+1) architectures, market makers benefit from the power of multilateral netting. A liquidity provider can execute thousands of buy and sell orders throughout the trading day, yet only settle the net difference at the end of the cycle. In this environment, delayed settlement is not a bug. It is a feature. It functions as an implicit, interest-free credit facility that allows a single dollar of balance sheet to support hundreds of dollars in trading volume.

To put this concretely: In a T+2 environment, $1M of capital can support $100M+ in daily volume through netting. In T+0, that same $1M supports exactly $1M.

In a strict T+0 atomic environment, netting is eliminated. Every transaction requires gross settlement. To sell an asset, the inventory must be present at that exact second. To buy an asset, the cash must be pre-funded in the smart contract or the exchange account.

This shift creates a pre-funding constraint. Market makers are forced to fragment their capital across various venues to ensure instant execution. The velocity of capital slows drastically. Consequently, to compensate for this significantly higher inventory cost, market makers must widen their spreads. The technology is faster, but the economic efficiency degrades.

Liquidity Fragmentation and Basis Risk

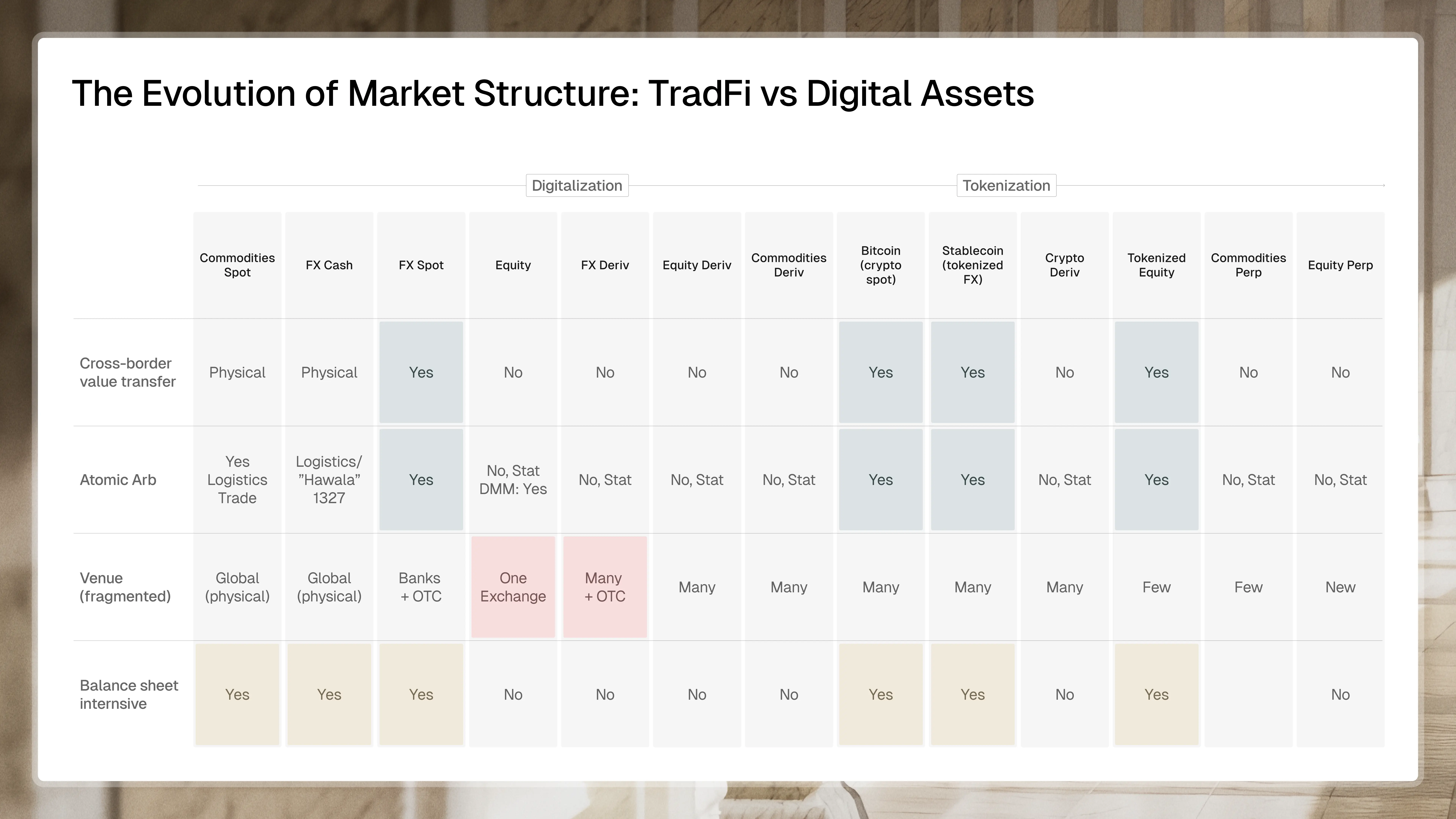

While tokenization improves the transferability of assets, it has currently resulted in market structures resembling the fragmented global FX markets rather than the centralized equities market

The "onchain" ecosystem is characterized by liquidity fragmentation A tokenized Treasury Bill on Ethereum and a tokenized Treasury Bill on Solana are legally identical but technically distinct assets. They cannot be netted against each other, nor can they effectively cross-margin without complex bridging.

This forces market makers to maintain redundant inventory across multiple exchanges and protocols to service order flow. This redundancy exacerbates inventory basis risk: the risk that price discrepancies will occur between the time liquidity is sourced and the time it is deployed across disconnected venues.

Legacy Settlement delay: A Feature, Not a Bug

We often criticize legacy financial systems for being slow, viewing the two-day settlement lag as a technological inefficiency. However, from a market microstructure perspective, this delay performs a specific economic function: it acts as a financing mechanism

Delayed settlement effectively functions as an unsecured intraday credit facility provided by the market infrastructure. It allows liquidity providers to turn over the same capital multiple times before the settlement obligations mature. By removing this delay in the name of safety and speed, we are essentially stripping the market of this implicit leverage. We are replacing a credit-based system with a cash-based system, which is inherently more expensive to operate.

The Missing Link: The Capital Efficiency Layer

This brings us to the critical challenge of the transition era. We are moving toward a T+0 world because users demand the user experience (UX) of instant gratification and the safety of trustless settlement. Yet, the economics of market making still require the capital efficiency found in netting regimes.

Technology alone cannot solve this economic friction; only capital can.

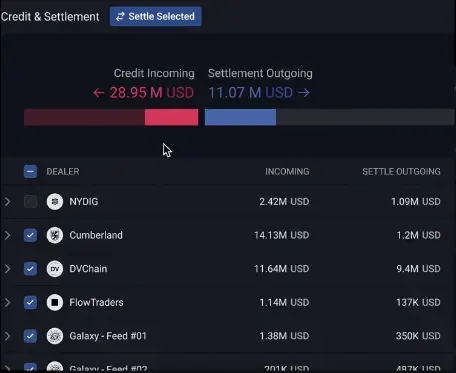

To bridge the gap between the efficiency of T+2 and the immediacy of T+0, the market requires a new type of intermediary: a Capital Efficiency Layer. This role must be filled by institutions willing to deploy their Balance Sheet to absorb the inefficiencies of atomic settlement.

These intermediaries act as the principal counterparty. They utilize their own capital to pre-fund the instant settlement that fintechs and users demand, effectively re-introducing the credit that atomic settlement removes. In doing so, they allow fintech operators to offer a T+0 experience without the crippling capital requirements.

Conclusion

The trajectory of finance is moving toward instant settlement.. However, the road to T+0 is not just a software engineering challenge; it is a financial engineering challenge. Without entities willing to bridge the gap with robust credit intermediation, the dream of instant settlement will come at the cost of wider spreads and thinner markets.

In a T+0 environment, liquidity becomes strictly a function of capital availability The pivotal infrastructure providers that can act as the bridge between capital providers and technology operators will define the infrastructure of tomorrow's markets.